A Practical Treatise on the Art & Craft of Plastering and Modelling

Including full descriptions of the various tools, materials, processes, and appliances employed; also moulded or “fine” concrete as used for fire-resisting stairs and floors, paving, architectural dressings, & and of reinforced or steel concrete; together with an account of historical plastering in England, Scotland, and Ireland, accompanied by numerous examples.

William Millar, Plasterer and Modeler

London 1897

Sgraffitto. – Sgraffitto or “graffitto” is an Italian word, and means “scratched.” Scratched decoration is the most ancient mode of surface decoration employed by man. The primitive savage of the flint-weapon period used this simple form of ornamentation. Scratched work, as used by prehistoric man, may be fitly termed the proem of the civilized arts of drawing, modelling, and sculpture. The term is now employed for plaster decorations, scratched or incised upon plaster or cement before it is set. It may be used for both external and internal decoration. The annexed illustrations (Nos. 65 and 66) will demonstrate the high degree to which the art of sgraffitto attained in Italy. Good English examples are to be seen at the Choir Schools of St Paul’s Cathedral and the School of Music, near the Albert Hall. Different methods and materials for sgraffitto are to be seen at the Science and Art Schools, South Kensington. This experimental work was executed by the art students in 1871, from designs by T. W. Moody. The work covers a large area of exterior wall surface, with a great variety of artistic designs and execution. The colours in the greater portion of the work retain their original freshness. In a few instances the colours in the panels have faded. This is probably due to the materials experimented with.

Some of the graffittos at South Kensington are really low relief work rather than sgraffitto, they being very deep cut with the iron or steel point, which was necessitated by the final coat being plastered on instead of washed on. Deep cutting gives a hard appearance to the design, prevents the water from running off the walls, and catches the dirt. In executing true sgraffitto, the cut or scratch should be exceedingly slight—in fact, in some parts scarcely perceptible. At South Kensington the work is a little darker than when first executed, still it is perfectly distinct. Time seems to have given it a finer tone.

These examples afford good evidence that sgraffitto decorations do not suffer materially from time and atmospheric changes. Sgraffitto is extensively used on the Continent, especially in Germany and Italy. Its limited use in Great Britain is probably due to erroneous impressions that it would not resist our variable climate, and that it would prove too expensive for general use. Examples herein named tend to prove that it is a durable and inexpensive decoration.

Vasari says:

“Artists have another art, which is called graffitto. It is used to ornament the fronts of buildings, which can thus be more quickly decorated, and gives greater durability and resistance to rain, in consequence of the etching on the wall being drawn in colours. The cement is prepared and tinted, and forms the background, and is subsequently covered with a travertino lime-wash, the lines being afterwards scratched in with an iron stilus.”

“Backgrounds are obtained,” the same author says, “by the entire removal of the surface wash,” and he describes how strong projecting shadows for foliage, fruit, and grotesque figures may be obtained by adding stronger shades of the colour to the background. In some backgrounds, colours in monochrome are sometimes added, and these are treated in a similar way to fresco. This is simple after experience has taught the difference between the tint in its wet and dry state. Fine and rich effects are obtained by the addition of gilding to some of the prominent parts of the design. The gold, however, must be added when the sgraffitto is perfectly dry. When properly manipulated, sgraffitto is quite capable of resisting heat, rain, and frost, because it offers a very hard surface, and is much less porous than ordinary stones or bricks. It can also be easily washed when begrimed by smoke or fog. As to a question of cost, it will compare favorably with any other external decoration.

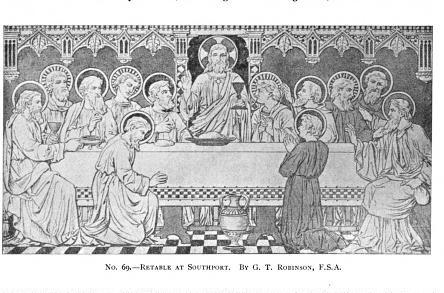

The beautiful examples of sgraffitto work, shown in the annexed illustrations (Nos. 67, 68, and 69), were designed by and executed for Mr. G. T. Robinson, F.S.A. These highly artistic works should amply demonstrate and convince the most skeptical as to what can be done in this mode of decoration; also that our British artists are not behind their foreign rivals both in conception and execution.

These examples are a combination of sgraffitto with fresco, and I cannot do better than give the modus operandi in the artist’s own words:

“In my own practice as an architect and decorator, I have, during the last fifteen or twenty years, used sgraffitto somewhat extensively for both external and internal adornment, and most of that which I have done is still in perfect condition, even in grimy London. The mode adopted has nothing new in it; in fact, Vasari’s instructions hold good to this day, excepting that I use ordinary materials, and find the simplest the best. The wall is prepared in the ordinary way. A rough coating of Portland, mixed with three times its quantity of good sharp sand, is, for external work, laid on and finished with a roughened surface, by stubbing it with an old birch besom, leaving it barely half an inch from the finished face. For internal work, the ordinary pricking up suffices. When this is dry, a thin coat of selenitic lime, mixed with the desired colouring matter for the background, is floated over it. This background may be black, bone-black being used; red, for which you may use Venetian or Indian red, or the ordinary purple brown of commerce, singly or mixed, to produce any tone you may desire; yellow, produced by ochres or umbers; blue, by German blue, Antwerp blue, or any of the commoner blues, avoiding cobalt, and these colours you may use to any degree of intensity or paleness. When this coat is nearly dry, you skim over it a very thin coat of pure selenitic lime, which dries of a parchment colour, and generally suffices. If you want a pure white lime, use a moderate quick-setting one, as stiff as you can work it, and as each variety of lime has its own individual perversity, I can give no general direction, and would advise the beginner to stick to selenitic, which is always procurable.

You have, of course, prepared your cartoon. This is pricked and pounced as for any other transfer process, and then with an old, well-worn, big-bladed knife, for there is no better tool, you can round all the outlines, and with a flat spatula clear away all the thin upper coat, leaving the coloured ground as smooth as you can. If your plaster is not quite dry enough for the two coats to separate easily, wait a little longer, but not too long, for that is fatal. By the time you have cleared out your background, the plaster will be in a good condition to allow you to cut out the finer parts of the design, such as the folds of the draperies, or the finer lines of the faces or of the ornament. Use your knife slightly on the slope, and if you want to produce half-tones, slope it very much; but, as a rule, the more you avoid half-tones, and the simpler and purer your line, the more effective your work will be. Recollect, above all things, you are making a design and not a picture, and you must never hesitate, for to retouch is impossible. Sometimes it may be desirable to gild the background, and you can then carve or impress it with any design you choose. It occasionally happens you want to give some semblance of pictorial character to your work when it is small in scale and near the eye, and then you can proceed as though you were cutting a wood-block. The series of the Four Seasons in a porch at Maidenhead (illustrations Nos. 67, 68) illustrate this treatment.”

“By cutting out your ground colour in places, and plastering it with that of another colour, you may vary any portion of it you desire. You can also wash over certain parts of your upper coat with a water-colour if you desire, combining fresco with sgraffitto, both of which manners are used in the Southport retable (illustration No. 69); but, as a rule, the broader your design, and the simpler your treatment of it, the better. It will be seen that this process is very available for simple architectonic effects; and for churches, hospitals, and other places where large surfaces have to be covered, it is the least costly process that can be adopted. It has also the great advantage of being non-absorbent, and it can be washed down at any time.

At Messrs Trollope’s establishment in London there is a specimen which for two years was fixed up outside their heating apparatus chimney, exposed to all weathers, under the adverse circumstances of rapid changes of temperature, and it was naturally encrusted with soot. It has simply been washed, and presents a very fair illustration of how enduring this mode of decoration is, and how well fitted for external decoration of town buildings. The artist is untrammeled by difficulties of execution, but he should bear in mind that the more carefully he draws his lines, and the simpler he keeps his composition, the more charmed with the process he will be, and the better will be the effect of his work.”

Mr. Heywood Sumner, a well-known artist, records his experience of sgraffitto as follows:— “Rake and sweep out the mortar joints, then give the wall as much water as it will drink, or it will absorb the moisture from the coarse coat, as it will not set, but merely dry, in which case it will be worth little more than dry mud. Care should be taken that the cement and sand which compose the coarse coat should be properly gauged, or there may be an unequal suction for the finishing coats. The surface of the coarse coat should be well roughened to give a good key, and it should stand some days to thoroughly set before laying the finishing coats. When sufficiently set, fix your cartoon in its destined position with nails; pounce through the pricked outline; remove the cartoon; replace the nails in the register holes; mark in with chalk spaces for the different colours, as indicated by the pounced impression on the coarse coat; lay the several colours of the colour coat according to the design as shown by the chalk outlines; take care that in doing so the register nails are not displaced; roughen the face in order to make a good key for the final coat. When set, follow on with the final surface coat, only laying as much as can be cut and cleaned up in a day. When this is sufficiently steady, fix up the cartoon in its registered position; pounce through the pricked outline; remove the cartoon, and cut the design in the surface coat before it sets; then if the register is correct, cut through to different colours, according to the design, and in the course of a few days the work should set as hard and as homogeneous as stone, and as damp-proof as the nature of things permits.

“When cleaning up the ground of colour which may be exposed, care should be taken to obtain a similar quantity of surface all through the work, so as to get a broad effect of deliberate and calculated contrast between the trowelled surface of the final coat and the scraped surface of the colour coat. The manner of design should be founded upon a frank acceptance of line, and upon simple contrasts of light against dark, or dark against light. The following are the proportions of the various coats:—

“Coarse coat – of Portland cement to 3 of washed sharp coarse sand.

“Colour coat – of air-slaked Portland to 1 of colour laid ^ inch thick. Distemper colours are Indian red, Turkey red, ochre, umber, lime blue; lime blue and ochre for green; oxide of manganese for black. In using lime blue, its violet hue may be overcome by adding a little ochre. It should be noted that it sets much quicker and harder than the other colours named.

“Final coat, internal work – Parian, air-slaked for twenty-four hours to retard its setting, or Aberthaw lime and selenitic sifted through a fine sieve.

“For external work – 3 selenitic and 2 silver sand.

“When finishing, space out the wall according to the scheme of decoration, and decide where to begin, and give the wall in such place as much water as it will drink; then lay the colour coat, and leave sufficient key for the final coat. Calculate how much surface of colour coat it may be advisable to get on to the wall, as it is better to maintain throughout the work the same duration of time between the laying of the colour coat and the following on with the final surface coat; for this reason, that if the colour sets hard before laying the final coat, it is impossible to get up the colour to its full strength wherever it may be revealed in the scratching of the decoration. When the colour coat is quite firm, and all shine has passed away from its surface, follow on with the final coat, but only lay as much as can be finished in one day. The final coat is trowelled up, and the design is incised or scratched out. Individual taste and experience must decide as to thickness of final coat, but if laid between \ inch and rV inch, and the lines cut with slanting edges, a side light gives emphasis to the finished result, making the outlines tell alternately as they take the light or cast a shadow.”

Another method which I have used in sgraffitto for external decoration was done entirely with Portland cement. This material for strap-work or broad foliage, or where minuteness of detail is unnecessary, will be found suitable for many places and positions. Three colours may be used if required, such as black for the background, red for the middle coat, and grey or white for the final coat. These colours may be varied and substituted for each other as desired, or as the design dictates. The Portland cement for floating can be made black by using black smithy ashes as an aggregate, and by gauging with black manganese if for a thin coat. The red is obtained by adding from 5 to 10 per cent, of red oxide, the white by gauging the cement with white marble dust, or with whiting or lime, the grey being the natural colour of the cement. After the first coat is laid, it is keyed with a coarse broom. The second coat is laid fair and left moderately rough with a hand-float. The suction of the first coat will give sufficient firmness to allow the third coat to be laid on without disturbing the second. The third coat should be laid before the second is set hard. The second and third coats may be used neat, or gauged with fine sifted aggregate as required. The finer the stuff, the easier and cleaner the work, and the cut lines are more accurate and free from jagged edges. The outlines of the design may be pounced or otherwise transferred to the surface of the work, and the details put in by hand. The thickness of the second coat should be about f\ inch, and the third coat about ^ inch. The thickness of one or both coats may be varied to suit the design. The beauty of effect of this method of linear decoration, aided by two or three colours, depends greatly on the treatment of design, the clearness of the incised lines, and the pleasing colour contrasts. It will be seen that in the three methods described there is a similarity, yet the method of using two colour coats on a dark floating coat will give more variety and effect. There is a large use for sgraffitto in the future, as it has been in the past, and its use is intimately bound up with the future of cement concrete.

In order that the foregoing examples of high-class sgraffitto may not deter the young plasterer from trying his ” ‘prentice han'” in this class of work, some simple designs are given in the annexed illustration (No. 70). Fig. I shows a design for a frieze in two colours. The ground may be black or red, and the ornament buff or grey. The coloured material for the ornament is laid first, and the coloured material for the ground laid last. Fig. 2 shows a design for a cove in two colours, one with two shades. The ground is grey, and the band work buff. A deeper shade of buff for the honeysuckle can be obtained by brushing this part with liquid colour made deeper than the original gauge, also by laying a black coat first, and in a line with the honeysuckle; then laying the buff stuff for the band work next, and then laying the grey colour last. In the latter case the honeysuckle is cut deeper than the band work, so as to expose the black coat.

The annexed illustration (No. 71) shows a design of an ornament with mitre for a panel moulding in two colours, the ground black and the ornament red. The red colour is laid first, and the black next. Other colours may be substituted as required. Illustration No. 72 shows a design for a frieze or a panel ornament in three colours with shading tints. The first ground (1) is dark brown, the second ground (2) buff, and the fleur-de-lis leaf work (3) white or a light grey. The paterae and balls are also white or grey, with a black ground. The band work is the same colour as No. 2 ground. This may be tinted a darker shade by brushing it with a darker solution than used for the ground. Different effects can be obtained by changing the colours. Sections of the surface of the frieze and part of the moulding are shown at the ends.

Designs for sgraffitto borders are depicted in the annexed illustrations (Nos. 73 and 74). These designs are bold and effective, and are composed, in two colours.