An Architectural Museum on the St. Louis Riverfront

Bob Moore, Historian, Gateway Arch National Park

Part of the original concept for Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, the riverfront park commemorating St. Louis’ role in the westward expansion of the United States, involved the creation of a Museum of American Architecture. The process was long and convoluted, and eventually the dream of such a museum, chiefly championed by architect and preservationist Charles E. Peterson, was dashed. But between 1936 and 1958, the prospect of a national museum of American architecture was very real, and a collection of architectural materials was amassed to fill it. This article tells the story of the museum and of the eventual diaspora of materials which were once part of the collections of what has now been renamed Gateway Arch National Park.

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial was created by presidential proclamation on December 21, 1935. The National Park Service was authorized to oversee memorial planning, and a superintendent, John L. Nagle, was assigned to St. Louis in 1936. Charles Peterson, who had already founded the Historic American Buildings Survey within the Department of the Interior, was appointed project planner for the new park, and, in his own words, “engaged landscape architect Daniel C. Fahey of the National Capitol Parks Region as his assistant. Together Fahey and [Peterson] drove from Washington to St. Louis over the great National Road (US Route 40) in June of 1936. They opened their offices using packing boxes as furniture until desks, chairs and drafting room equipment could arrive.”1 The offices were located in rented space in the Buder Building on Seventh Street. At the time, the National Park Service did not have title to a single square foot of land in St. Louis, as none of the properties along the riverfront had yet been acquired.

Upon arrival in St. Louis, Peterson became acquainted with the plan for the new memorial outlined by civic leaders, headed by a local lawyer, Luther Ely Smith of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association, which was a federally-chartered organization. The plan was to raze all of the buildings within a 37-block area of the riverfront, encompassing Poplar Street north to Washington Avenue and Wharf Street west to Third.

St. Louis Star-Times, July 29, 1936, included portrait photos of the new memorial’s National Park Service personnel, including Superintendent John L. Nagle, Charles E. Peterson, Daniel C. Fahey and James E. Rasbach. Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

Luther Ely Smith, National Park Service Photo, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

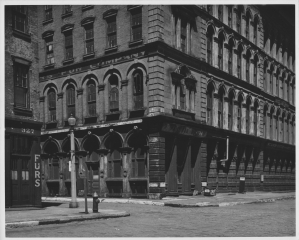

The National-Scotts Hotel, National Park Service Photo V106-003078, c. 1937, taken from the corner of Market and Third Streets looking SW, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

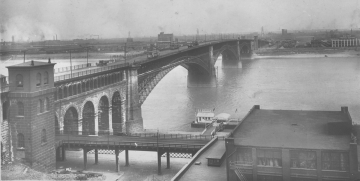

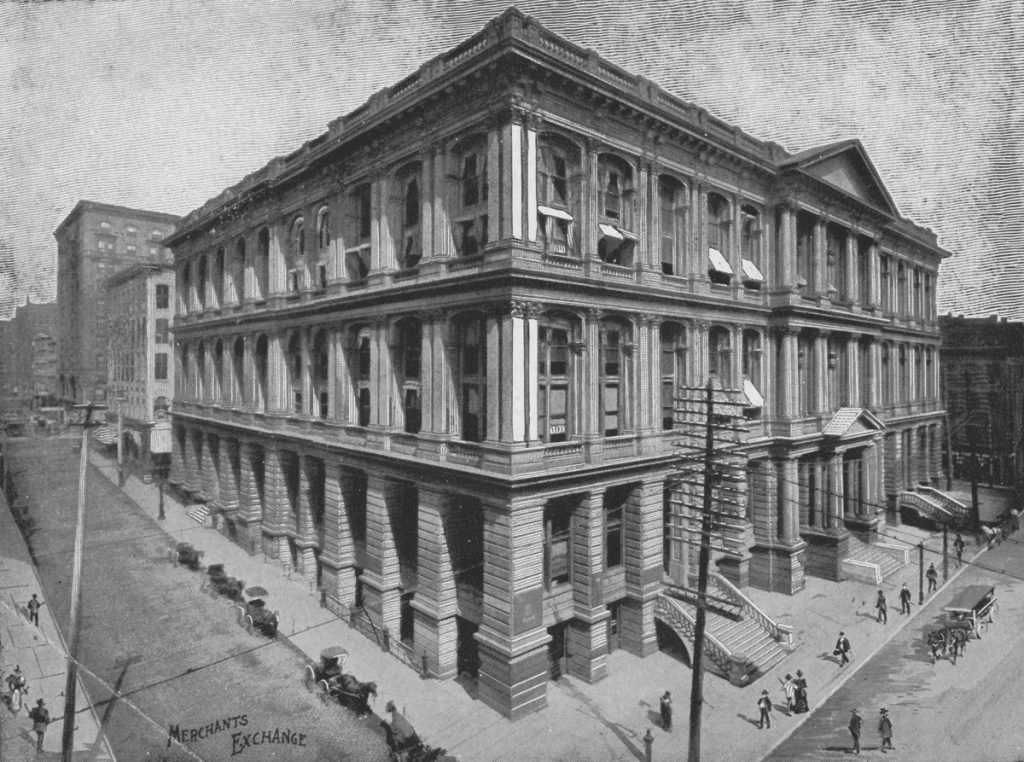

The Second Merchant’s Exchange Building (built 1873-1875), from photo by Sanders & Melsheimer, before 1910. National Building Arts Center collections.

V106-001989, The Jean Baptiste Roy House, mid-block on Second Street between Plum and Poplar looking west, National Park Service Photo, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

In his 1994 oral history interview, Peterson was very respectful and full of admiration for park founder Luther Ely Smith, but very much opposed to his thought process and tactics regarding the memorial project. “Luther Ely lived on Waterman Place, I lived on Lindell Boulevard. Now, the Smiths were extremely kind to me, the whole family. We had two different relationships. . . . [I liked him] on one level, but, I used to ask [Philadelphia architect] George Howe, who [was the advisor for] the 1947 competition, I said, ‘Why is it that Luther Ely Smith is so opposed to saving any old buildings down there?’ He said he just didn’t know. He wondered the same thing. See, [Smith] wouldn’t let us save, at no expense to him, the Roy House, which was two blocks [south of the memorial site]. Joe Desloge was ready to pay the bill for moving it and restoring it, the owners wanted to get rid of it, and it had this wonderful connection with the early French up the Missouri River and all that. Luther Ely Smith, without saying anything, killed the project. And it was a genuine original. You can be related to people in two entirely different ways, and [those ways] can be antagonistic. . . . “4

Because there were disputes over the condemnation by the City of St. Louis of the land parcels in the memorial area, court battles lengthened the time between concept and execution of the plan to take down the riverfront buildings. This gave Peterson time to assign personnel to research the past history of the site, conduct architectural investigations of the structures and use of materials on the St. Louis riverfront, and speak publicly in an effort to try to prevent the wholesale destruction of an important set of mid-19th century buildings. As Peterson related, writing in the third person: “Upon his arrival in St. Louis in 1936, the author immediately began to acquaint the city’s citizens with the National Park Service’s mission to preserve historic sites and buildings, especially as it pertained to the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. In addition to preserving buildings in situ, or recording them prior to demolition, our purpose was to show how American buildings reflected the society that built them. Another objective was to make sure that the Mississippi Valley be well represented in the proposed Museum of American Architecture. The St. Louis press and its citizens responded with interest.”5

One of the chief ironies was that the memorial was created to describe St. Louis’ role in westward expansion, yet most of the still-extant buildings slated for destruction were witnesses to those very events. But the civic leaders wanted all of them torn down. Peterson made lists of outstanding and representative buildings that should be allowed to stand, lists that dwindled in numbers as he was told that all was to go. He was successful in preventing the removal of the Old Cathedral from its original site with the idea of rebuilding it at the southwest corner of Market and Third (where the KMOV Building stands today), and also in advocating for the restoration and preservation of the 1818 Old Rock House.

Riverfront pre-demolition, aerial view taken c. 1939 with superimposed dashed line showing the extent of the memorial development, National Park Service Photo, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

A Museum of American Architecture

Charles Peterson’s thought process led to a couple of early conclusions. Demolition of the riverfront buildings was a tragedy, but no one could stop the staff of the memorial from assessing the structures and earmarking specific architectural features that might be salvaged. As he and his staff studied the riverfront more closely, they came to realize that important aspects of the use of cast iron as a building material were represented there. Although the French-era vertical log and masonry structures were gone (the last was torn down in 1875), the riverfront buildings represented a microcosm of American architectural heritage and building techniques between 1818 and 1880. Architectural fragments salvaged there might be brought together and used as exhibits in a Museum of American Architecture. Since nothing quite like this existed anywhere in the United States at the time, the concept of a museum of architecture was somewhat revolutionary. In addition to telling the story of the St. Louis riverfront from an architectural perspective, materials and fragments from other areas of the U.S. could also be purchased or acquired on loan and displayed in the museum to present a comprehensive narrative of the architectural heritage of the nation.

These ideas occurred to Peterson very early in his tenure on site, as evidenced by this 1936 newspaper article, written less than two months after his arrival in St. Louis:

Two Museums, Depicting Early Fur Trade and Growth of Architecture, May Be Nucleus of River Memorial

. . . Would Restore Buildings

The Peterson plan looks to a restoration of typical early buildings where available, to the reproduction of others that have been destroyed, and to the erection of typical groups from the early American [era], and their European prototypes.

“Not only would this museum contain actual buildings, but an almost endless array of objects showing detail of architectural beauty and utility. It would seek to do, in a more general way, what has been done at Dearborn and Williamsburg.”

Specifically, the Peterson plan would show what Thomas Jefferson did at the University of Virginia, of which he was the father; what the first pioneers did in erecting their homes of vertically placed logs, with vast contributions lying between these extremes. As Peterson envisions the plan, no museum of the kind would be comparable to it.6

Charles Peterson outlined his plan in great detail in the November 1936 issue of the Octagon (link to full article):

“The Memorial must tell of the westward development of the country. What more graphic expression of political and social history can be found than the builder’s art? The meeting house of New England, the planter’s mansion of the South, the log cabin of the Western pioneer, the hacienda of the Southwest and the log fort of Alaska relate a more forceful story than any arrangement of words. The nature of the American people and the chronology of their movements are permanently recorded in their structures. . . . The purpose of the Museum of American Architecture would be to conserve for the benefit and enjoyment of the people their heritage of architectural achievement.”

It should be remembered that Mr. Peterson’s proposal was radical in its time for several reasons. Few museums collected or displayed specimens of architecture at that time, and the open-air museum of the type exemplified by Williamsburg and the Henry Ford Museum (Dearborn Village) was just getting started with those institutions. As Peterson noted, the National Park Service in 1936 had but 25 buildings from the historic period which it was preserving “scattered from San Diego to New York. But neither this movement, nor any other will be able to preserve the greater part of our ancient structures which will go down from lack of maintenance, mechanical obsolescence or other economic causes. The least that can be done is to record them for the archives before they disappear, and to preserve such fragments as may be of particular interest. The Pictorial Archives of Early American Architecture and the Historic American Buildings Survey have made a good start on the former. The proposed Museum of American Architecture would supply the latter need . . .

There should be some means of studying the whole range of American architecture comparatively. While our libraries—notably the Library of Congress with its complete collection of books and the Historic American Buildings Survey records—offer opportunities for the research worker to dig out the facts and make his own comparisons, the layman is not going to find out what American architecture is by that method. The material to tell the story must be gathered in one place where it can be arranged in a graphic manner.

A Museum of American Architecture as a research unit would be a well-nigh indispensable help to the architects in the general program of the National Park Service for the physical study and preservation of government owned buildings in historical areas throughout the country. At the present time there is no general agency of this kind—either public or private.”

In his Octagon article, Peterson went on to describe the exhibits and amenities of the proposed museum in some detail:

The museum would have at least six different types of exhibit—each of interest to both the scholar and the general public: (1) entire buildings, (2) parts of buildings—specimens of construction and ornament, (3) small scale models of buildings, (4) specimens of drawings by architects and builders, especially those made for important competitions, (5) photographs of buildings, (6) craftsmen actually working materials in the ancient traditions.

The use of entire antique buildings at St. Louis would be limited to local types connected with the early years of the city. The first phase of development was the French house on which considerable data is available. Examples still exist in certain parts of Illinois and Missouri. There are a number of stone mansions of the early 19th Century American type which might be acquired for the Museum. Most of them are now threatened with destruction. Like the French houses they have disappeared from the riverfront before the St. Louis building boom of the steamboat period. Certain good examples of early brick buildings should also be secured. It is possible that a limited area at the south end of the [memorial site] could be used for such purposes. It would be contrary to the policy of the Museum to cause any buildings important as historic sites or landmarks to be moved from their original location. On the other hand, good examples of architecture which would otherwise disappear would be accepted whenever possible. . . .

The collection of examples of architectural ornament would be one of the most important functions of the Museum. Collections from Greek and Roman and even Egyptian and Assyrian ruins have enjoyed a considerable vogue since the Classic Revivals in architecture. . . . Architectural ornament from this country is seldom seen in such collections, and it is a regrettable omission. We have produced work here which should be at least as interesting to Americans as that of the ancient Mediterranean countries.

The Geffrye Museum of London is an institution operated by the County Council which conserves select fragments of construction and decoration from London buildings demolished to make way for civic improvements. By careful study they have been able to arrange series of specimens of paneling, hardware, balusters, and other architectural parts from the earliest times to the present. Such arrangements illustrate strikingly the evolution of building craftsmanship as well as of architectural design. . . .

The collection of the structural and ornamental parts of buildings would have a splendid start using selected fragments from the more than four hundred buildings to be razed before the construction of the Memorial. Specimens illustrating a period of one hundred years can be acquired during the demolition for no more work than pains to select and store them in study rooms. Cast iron facades of great merit exist in numbers—the St. Louis riverfront may well contain the finest collection in the country. It might easily be supposed that there is plenty of such material now existing throughout the country, and that it is not valuable enough to be housed in a museum. Observers, however, report that the earlier examples are getting noticeably scarce and it seems time that comprehensive collections were being organized. . . .

A study of the structures under discussion will show that they are mostly warehouse and loft buildings with their architectural interest confined to their street fronts. Since these facades are of limited cubage, it would be possible to arrange some of the more interesting examples within the museum building without affecting its exterior design. . . .

The model exhibits would form perhaps the most valuable part of the museum’s displays. These would show, in ample series of juxtaposed specimens at uniform scale, the evolution of the various types of buildings found in the United States. Conceivably these could start with the European prototypes familiar to the early colonists and show, for instance, the relationships between England and New England, France and Louisiana, Holland and New York, Spain, Mexico and California, Germany and Pennsylvania, and several others. The series could be carried down to modern times showing some American innovations which have influenced European work and then come back to us in the ‘International’ style.

Before any model is constructed, accurate and detailed measurements would be taken from the original structure and the complete records prepared for the Historic American Buildings Survey with detailed monographs on each. Models would be precisely constructed under the direction of recognized archaeological specialists. . . .

At the present time there seems to be no public agency which is making an organized effort to collect old drawings by architects and builders. The earliest of these are rather rare, but they can be represented in facsimile where there would otherwise be gaps in a complete series of specimens. The Museum might act as a repository for the drawings of national architectural competitions. Had such a facility been available sooner the Federal Government would have today the original drawings for the United States Capitol and the White House from the competition of 1792.

A good collection of photographic enlargements of architectural subjects would be a valuable supplement to the other exhibits. With photographs it will be possible to cover a vast range of material hardly possible in any other way. The Pictorial Archives of Early American Architecture in the Library of Congress have a fine collection of negatives from which enlargements can be made. There would be a large number of new photographs acquired in the course of the general research program. The publication of picture books of American Architecture on a large-edition, low-retail price basis could become a valuable factor in the field of general education.

The exhibitions of early craftsmen plying their trade would be popular points of interest for the general visitor. The making of handmade brick, the blowing of window glass, the working of iron and wood—of which the original methods are all but forgotten—could be carried on with the old tools and in the old backgrounds. The operations themselves might be let out by concession so that the products could be sold to pay for the work.

It would be quite possible to expand the activities of the Museum to include the related fields of city planning, landscape design and interior furnishing. . . .

The Museum would constitute a unit of the National Park Service. It would be administered by a Director who would report directly to the Director of the bureau, and thus indirectly to the Secretary of the Interior. He would be an architect with special experience in the field of historic architecture, as would most of the staff. All would pursue original lines of research for publication by the Museum.

The Director of the Museum would be guided in general policy and in the acceptance of donations by an Advisory Council appointed by the Secretary of the Interior, of persons of recognized standing in the field of historic architecture or specially related museum activities.7

Peterson and his team tried constantly, and through different inventive means, to bring their case for saving St. Louis’ architectural heritage before local residents. But the original plan for the memorial dealt only with commemorating westward expansion through a physical, created monument and park. It was not concerned with the physical remains of the era embodied in the riverfront structures being razed – or even with the preservation, either physical or in writing, of the heritage that would be lost. “To make the public aware of research on the project area,” Peterson remembered, “an exhibit entitled ‘The Old St. Louis Waterfront’ was held at the St. Louis Public Library in April 1938. In the exhibit’s catalog we articulated the main objective of our work for the past two years: ‘to attempt a thorough understanding of those physical remains in the thirty-seven blocks of riverfront buildings which will be razed, in order that important historical objects not be discarded through lack of information.’”8

Plan 8009

In addition to disseminating his ideas regarding a Museum of American Architecture, Charles Peterson had a second scheme which he felt could embed his idea within the framework of planning for the new memorial. He wanted to take the high ground in advance of memorial development, which the city fathers stated would be driven by the result of an architectural competition. This left a big question mark in terms of what would be designed, and even what would be described in the official program supplied to guide competing architects. Knowing that the influences on the local memorial proponents stemmed from the City Beautiful Movement and the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, Peterson realized that axial relationships, vistas, monumental structures, iconographic focal points and water features would all figure prominently in their thinking.

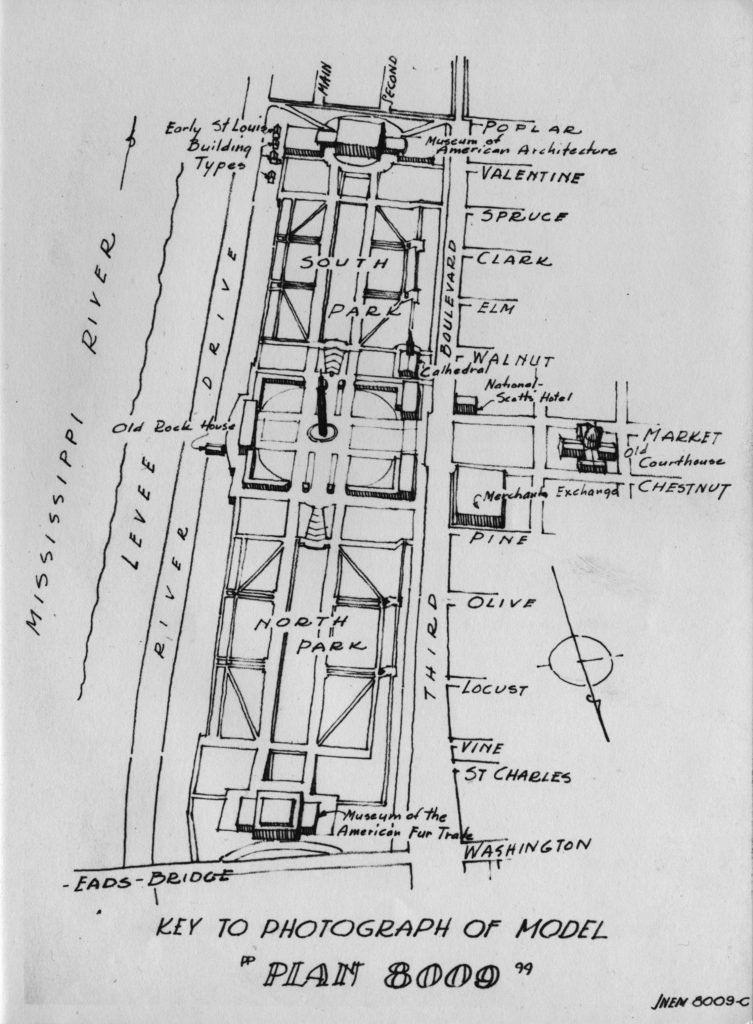

Plan 8009 Drawing, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

Plan 8009 Plasticine Model, photograph, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

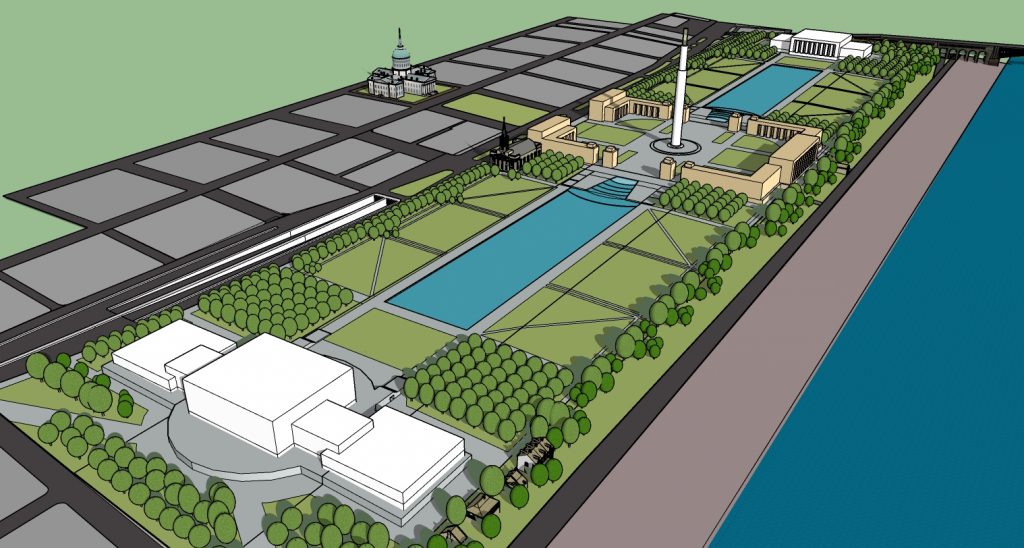

As a result, he and his staff came up with their own plan for the memorial area which included all of these features and had prominent places set aside at the north and south ends for a Museum of the American Fur Trade and a Museum of American Architecture. They called their idea “Plan 8009” and made drawings and a large scale model out of plasticine clay. The model was ready by October 1937, and it was a fresh approach to the memorial concept that was hard to ignore. The attention to detail and deep thought that went into Plan 8009 is evidenced by Peterson’s comments on it, which were made near the end of his life in 2002:

Plan 8009 consisted of a major north-south axis parallel to the Mississippi River and a minor axis linking the river to the Old Courthouse. The Memorial was divided into three sections; the South Park fronting the Museum of American Architecture and North Park fronting the Museum of American Fur Trade. Uniting the scheme at the axial crossing was a Central Plaza, containing a tall slender tower or shaft as the focal point. Taking advantage of some of the then new lighting techniques, a central tower was designed with a crowning element of moulded glass that was to be internally and externally illuminated. To provide an architectural frame for the Plaza, a colonnaded porch surrounded it, facing inward. A parking garage was to be located underneath the Plaza.

The two museums terminated the major axis. In addition, the designers retained the Old Courthouse, Old Cathedral, the Rock House, and National-Scotts Hotel, the most significant historic buildings on the site, as part of the scheme. Unfortunately, only the Old Courthouse and Cathedral survive today. The original pattern of streets was to be recalled in the pattern of pedestrian walkways. Although only a sketch, Plan 8009 influenced the program for the architectural competition held after World War II.

Over five hundred existing buildings were surveyed during the early years of the project. Most were scheduled for demolition. Of these, a number had interesting features that staff architects felt should be saved for the proposed architectural museum. The Superintendent agreed. Thus, when demolition of the site started in October 1939, the contracts specified what should be saved and delivered to the Park Service for storage. These varied from small decorative elements to four complete cast iron facades, considered excellent examples of the structures erected immediately after the 1849 fire.”9

Peterson mentioned the four complete facades once again in his oral history, stating that: “We took down four whole cast-iron facades, unscrewed them carefully. And they would have been the courtyard of the Museum of Architecture. The four facing in instead of out.”10

In the description and explanation of Plan 8009 written in 1937, the Museum of American Architecture was described in this way:

“(1) This building, with the Eads bridge, serves to stop the major axis of the Memorial at its South end.

“(2) The central block of this structure is four stories high with lower flanking wings. The building contains approximately three million cubic feet.

“(3) The public entrance to this structure is on the north, or inner, side. It is reached from the rear by a circular drive for the special convenience of buses and of those automobilists who wish to get a view of the central motif down the reflecting pool.

“(4) The growing study collections of this Museum would in the future be accommodated in low flanking buildings. The site of these would be used for parking at the present time.”11

Plan 8009, #3 and 6, views from 3D computer model created by Bob Moore in 2018.

Details of the Museum of American Architecture

In November 1936, the same month as the publication of his article in the Octagon, The American Institute of Architects passed a resolution commending and in support of a Museum of American Architecture in St. Louis:

Confident that the great body of American architects indorses the project of the United States Government and the City of St. Louis to build on the banks of the Mississippi, a splendid memorial to commemorate the Louisiana Purchase and its great promulgator Thomas Jefferson, and doubly conscious of the fact that Jefferson was architect as well as statesman and as such influenced the architecture of his country to a greater extent perhaps than any other – and furthermore agreeing wholeheartedly with the intent that this noble plan shall be no more display of symbolic architecture but rather of a character that will result in love of country through knowledge of its accomplishment, therefore be it resolved that the Board of Directors of the American Institute of Architects indorse the project of constructing and dedicating a great building as part of the Jefferson Memorial to the purposes of a Museum of American Architecture in which this and future generations of our countrymen may learn of the rise and spread throughout the years and throughout the land of the art and science of Architecture in the United States of America.12

Some specific displays described in papers prepared by Peterson and Bryan in the late 1930s give us some idea of what they had in mind for the structure they envisioned. These included a study of the sod houses of the prairie, a study of the log cabin as it evolved in the United States, and the reconstruction of façade of the Third Street elevation of the Custom House and Post Office.

Section View of the Custom House and Post Office (built 1852-1859, A. B. Young, architect) by George I. Barnett, Photo by Bob Moore, in the collections of Gateway Arch National Park.

V106-002881 Custom House and Post Office with façade stones marked for possible reconstruction after demolition, 1941, National Park Service Photo, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

Custom House and Post Office, c. 1941, National Building Arts Center collections.

A document in the archives of Gateway Arch National Park provides an in-depth look at their plans:

CONCERNING A MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE PROPOSED FOR THE JEFFERSON NATIONAL EXPANSION MEMORIAL

November 1937

THEORY OF THE LAYOUT

There is no reason why a Museum of American Architecture could not be highly enjoyable and instructive to the public. To win such a reputation, however, it must be more than a mere storehouse to which the public is admitted.

By (1) cutting down the quantity of material displayed in the public rooms and (2) showing the various items in such a graphic manner that a lesson can be learned from each exhibit the objective of the Museum can be realized.

It is proposed to divide the collections at St. Louis into three groups based on the qualifications of the visitors themselves:

(1) A one-hour circuit for the greater part of the visitors. It is assumed that they will have intelligence and curiosity, but that they have never before been instructed or interested in architecture. Those arriving in buses on escorted tours of the city will be able to make this trip which would include several houses in an out-door group.

(2) An assemblage of exhibits for those persons who would want to spend one day in the Museum. This group would include persons interested in historical and antiquarian subjects, those intending to build in a period style, architects, writers, painters and others. The level of education in this group would correspond to that of the visitor for which the “Early American Rooms” of some well-known American museums of art have been prepared.

(3) Study collections of architectural parts valuable to those making special researches. While this group of objects would eventually be large in size, it would normally be locked up and available only on special permission.

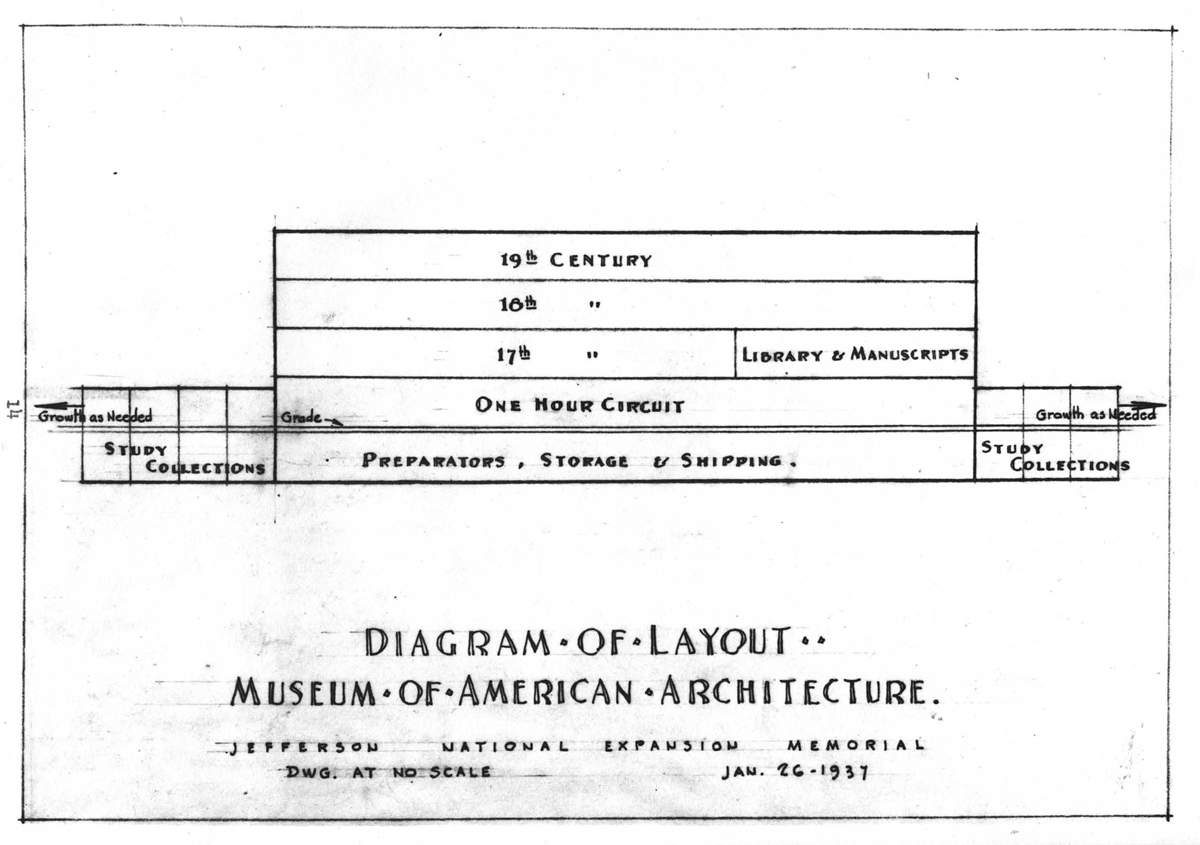

It seems to follow that the old palace-museum type of layout with its miles of aisles would not be suitable here. A four-floor diagrammatic section of the proposed central building follows.

Diagram from the paper “Concerning a Museum of American Architecture Proposed for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, November 1937,” RU 106, Series 9, Planning Records, Subseries 9.3, Interpretation Records, Folder marked “B”, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

PICTURESQUE FRENCH COLONIAL HOUSES

St. Louis was a substantially built town before the first Anglo-Americans put in their appearance. The buildings were built in a peculiar style not known on our Atlantic seaboard. It was derived from that of Old France by way of Canada and the West Indies.

At the time of the transfer of Upper Louisiana to the United States there were nearly two hundred of these buildings standing. With rising land values, most of them were replaced by larger brick buildings before 1850. The last one was the Bienvenue house, destroyed in 1875. Because the old French houses are such a rare curiosity today it would seem worthwhile to restore examples of the three types in the riverfront area to recall the earliest days of the city. . . .

THE ONE-HOUR CIRCUIT

The one-hour circuit would consist of a walk through the first floor of the central block of the Museum building (45 minutes) and a visit to three small furnished houses in the out-door section (15 minutes). Such a visit would be practically a minimum, but it would leave the general visitor with some vivid impressions. A well illustrated handbook in a “newsy” style would supplement such a trip most effectively.

Among the exhibits would be:

(1) The English house in Early America. Series of models showing how English precedent prevailed in American buildings for two hundred years. Other styles flourished locally and then disappeared following English conquest.

(2) Story of the log cabin – did it come from Sweden?

(3) Story of the skyscraper – defining “skyscraper” and showing its origin in Chicago, together with the development of the mechanical services which made it possible.

(4) American Homes of Four Centuries. Groups of furnished interiors, one for each century, starting with a 17th century example from Massachusetts and possibly ending with a contemporary apartment layout such as might be found in almost any American city.

(5) Thomas Jefferson, Architect. Jefferson had, perhaps, more influence on American Architecture than any other single individual. This would be explained in models, photographs, etc.

(6) Capitols of the United States. This would embrace a group of models at uniform scale. It should be a stimulating show, one particularly interesting to visitors from other states.

(7) Gallery of Ten Important American Architects and Master Builders Associated with various Periods before 1900. A tentative list is Kearsley, Buckland, Latrobe, Bulfinch, Mills, Upjohn, Barnett, Richardson, McKim and Sullivan.

(8) Gallery of Presentation Drawings from Important Architectural Competitions to be shown as examples of the draftsman’s art.

(9) Men at work at the Early Crafts. The blowing of window glass, the blacksmith making hinges, the joiner making mantels, etc. would be shown in contemporary settings.

(10) A court on the main floor in which would be displayed the facade of the Old Customs House (now at Third and Olive) and at least three other facades from middle 19th century St. Louis buildings in the riverfront area.

(11) Three small furnished houses of early St. Louis. Suggested examples are: The French palisadoed house, the log cabin and the American stone house.

CAST IRON ARCHITECTURE OF THE ST. LOUIS RIVERFRONT

The boom days of the middle nineteen hundreds witnessed a tremendous expansion of St. Louis. Following the great fire of 1849 and the new vogue of cast iron in architecture, a great deal of this “fireproof” material was used. Hundreds of new commercial buildings were put up near the river.

Because in recent years the riverfront has declined as an active business center, most of these structures have been allowed to remain and St. Louis may have the best collection of architectural cast iron in the country.

While unkept and dirty, many are fine examples of design and deserve preservation. For the cost of moving alone, several good examples can be preserved in the MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE.

In clearing the area of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial there are some four hundred and sixty buildings to be disposed of. These cover nearly every period of the 19th century, and a number of them are significant in St. Louis history. Can the National Park Service, acting under the Historic Sites and Buildings Act, destroy all of this in one fell swoop? The MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE offers a way out.

ANCESTRY OF THE “AMERICAN” LOG CABIN

Between 1638 and 1655 the New Sweden Company established and maintained a group of small settlements along the Delaware. Most of the colonists came from central Sweden where the hewn log cabin was the rustic vernacular of buildings. From the beginning, the reports of the governors tell of the raising of log dwellings and forts. These Swedes were known as unusually skilled log workers by their Philadelphia neighbors.

Since the English, Dutch and French did not know the horizontal log house in Europe (and consequently did not use it in their earliest works) can we not assume that the log cabin as we know it today is a Swedish type introduced during the coast-wise trading of the Delaware colony?

Properly exhibited, the evidence should be most interesting. The true facts can probably be determined by further research in the archives of. Stockholm . . .

THE ALL DAY CIRCUIT

For lack of a better term the second group of exhibits of the Museum might he known as the “All-day Circuit”. In this are included those objects which would be shown to the visitor who is already specially interested in architecture. It would take approximately a day to inspect this unit.

The collection would be divided between the upper three floors of the Central building – one floor for each century – the 17th, 18th and 19th. (For some years collections of the 20th Century work would be merely placed in dead storage or the study collection.) This general arrangement was followed in laying out the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum in 1925 and seems to be the most practicable. The work of any one century would thus be immediately available without the necessity of walking through thousands of feet of corridors and galleries lined with confusing material related to other periods.

At the same time the examples could be kept in the proper geographical relationship. For instance, the Spanish work of the Southwest runs through the same centuries as the Atlantic Coast buildings. Should it be decided to place all Southwestern work in the Southwest corner of each floor, the whole Spanish story could be seen exclusively by using small intercommunicating stairways between the second, third and fourth floors.13

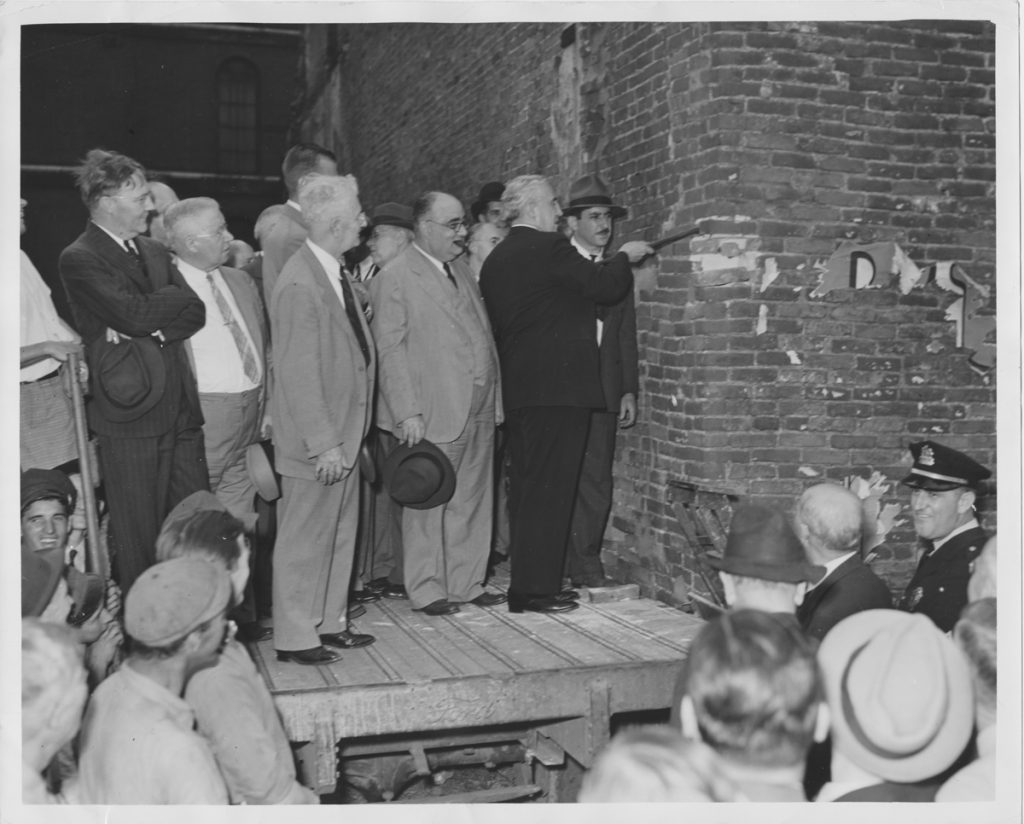

Mayor Bernard F. Dickmann of St. Louis begins demolition of 40 square blocks on 9 October 1939. Newspaper Enterprise Association photograph. National Building Arts Center collections.

Riverfront Demolition

By October 1939 all of the court challenges to demolition had been won by the City of St. Louis, the properties condemned and property owners bought out. Now came the time to begin demolition. Between 1939 and 1942 nearly every structure within the 37 block district was razed. One that was left standing was the Denchar Building, a one-story fireproof warehouse with a concrete floor located at the southern end of the grounds, in which the architectural fragments recovered during demolition were stored in anticipation of display in the Museum of American Architecture.

Denchar Warehouse interior, Charles Peterson (standing, 2nd from left) overseeing storage of recovered artifacts destined for the museum. National Building Arts Center collections.

In this photograph of the riverfront post demolition (3), the Denchar Building is still standing in the foreground. Memorial grounds from Spruce Street looking north, 1941, National Park Service Photo, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

In a 1993 interview Howard Gruber, an engineer on the project, recalled the building demolition.

[In the years prior to demolition] there were several teams of us who went out in pairs and visited each building, and took structural notes on the building; type of façade (many of them were cast iron) and the size of the building, and the number of floors and type of construction inside, which were used by some people in the office to determine the value of the buildings. After that when we had acquired all the buildings, I was out in the field working with the contractor, who was tearing down the buildings. . . . And it was interesting, in the demolition method, as they were all very old buildings, and the contractor, in my opinion, was an experienced wrecker. They made an effort to – before they started wrecking a block – to determine if there was, you might say, a keystone building in that block, that was in effect holding up the other buildings, because they were very old buildings, and if that was the case, they did not want to take that building down first, because of the several buildings leaning against it – not visibly leaning, but nevertheless supported by it. If they tore that one down first, several of them might collapse, and result in some injuries. So they had to work around that – tear that building down last. There were a couple of occasions when some buildings did collapse, although I don’t remember any serious injuries.

The Old Rock House . . . was torn down in a scientific way, and marked as to where things came from, and reconstructed . . . and [at a later date was] eventually torn down. But it was an interesting building, and it would have been nice if it could have been saved. It wasn’t. There were a number of pieces [of other buildings] saved, as a matter of fact, in many cases complete fronts, many of which were cast iron. They were stored in what was our office for a while, down in that area. And when that was torn down, in a larger building [the Denchar Warehouse] in the southern area. It was just full of artifacts; column tops, even complete columns, stone columns; a lot of cast-iron features and cornices, and things like that were saved. . . .

They photographed every building in the area, if I remember correctly. There was a formal photograph of every building [façade] in the area. And every building had a sheet that had all the details of the structure – the size of the building, the number of floors, the type of interior construction, the type of façade.

The general condition of the buildings down there was pretty bad. ‘Cause they were well-used, and they were old, and not much had been done to improve them at the time. There were some good ones, but there were [more] bad ones. [After the idea for the Memorial came up and progressed, the owners of these buildings performed minimal maintenance on occupied buildings and none in the empty ones].14

“[The Denchar Building] had a concrete slab floor and a delivery truck entrance. In this was stored a vast collection of carefully labeled artifacts intended for study and display in the Museum of American Architecture. The repository worked well until sometime during World War II when a bulldozer was used to quickly clear part of the storage area, damaging a part of the collection.”16 During the war Charles Peterson was in the U.S. Navy, serving on the staff of Admiral Chester Nimitz. A number of dangers confronted the collection during his absence, as outlined by historian Sharon Brown in her administrative history of the memorial: “During the war years, drives for scrap metal occurred frequently. In the interest of national security, [Superintendent] Julian Spotts had to maintain the position that these preserved pieces would be available as scrap if the military situation demanded. Fortunately, this never came to pass.”17

Deconstruction of Old Rock House in preparation for reconstruction, c. 1941, National Building Arts Center collections

V106-000214, Craftsman at work making shingles, 1941, Old Rock House restoration, National Park Service Photo, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

The 1947-48 Architectural Competition

Two years after the close of World War II, the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association sponsored an architectural competition to design a memorial for the riverfront. This citizens’ committee wanted to make the site an integral part of community life, and to create a modern and forward-looking space rather than an overly historic one, which was ironic in the light of the reasons the memorial was created. However, it is important to understand what the thinking of the city fathers led by Luther Ely Smith was. Their ideal was a riverfront park modern in conception and design which would present St. Louis as a city looking toward the future and not toward the past. Although elements of history would be incorporated into the memorial, the goal was to present a city open to change and welcoming to business and tourist dollars. It was an attempt to begin a civic rebuilding program which might recoup St. Louis’ past glories and position in the nation.

The competition was restricted to entries created by U.S. citizens and was held in two stages. The jury was composed of seven nationally-recognized architects, engineers and art historians, and preferred the modern or “international” style of architecture popular at the time. It was the first large competition held after World War II and offered a first prize of a then-whopping $40,000.

A 28–page competition program booklet was issued to all architects, engineers, artists and designers who expressed an interest in the competition. Written by local architect Louis LaBeaume, the booklet provided ground rules, criteria for designs, instructions on how to prepare and package entries, and a large amount of information on the history of the site, former structures that once stood on the site, and the various forms of architecture that once stood on the riverfront.

The competition booklet had this to say about museums for the site:

A MUSEUM OR MUSEUMS dedicated to interpreting the historic significance of the Site of Old St. Louis, the Louisiana Purchase, and the Westward Movement, is to be erected somewhere on the Historic Site. The cubage of the Museum or Museums shall be 4,000,000 feet for educational facilities, such as the display of objects and exhibits, as well as the interpretation of history by books, documents, and word of mouth, and every device for visual and oral education. Five hundred thousand cubic feet in addition are to be provided for the re-erection and display of architectural remains. The cubage is to be measured above grade. Appropriate spaces in the Museum or Museums are to be decorated with mural paintings illustrating or symbolizing the historic episodes interpreted by the exhibits. The nature of the spaces required for the educational program is left to the invention of Competitors, who are encouraged to suggest new educational devices and dispositions.18

A total of 172 architects or collaborative teams from across the United States responded. While well-known architects like Walter Gropius, Charles Eames, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, Louis Kahn, and Edward D. Stone submitted entries, it was the relatively unknown Eero Saarinen’s design and its soaring 590 foot tall arch that captured the jury’s imagination.19

Charles Peterson noted: “Although the competition was carried out by the Commission, it did not directly involve members of the architectural team that had labored so long and hard at the site [in the 1930s and early ’40s]. Many had been reassigned during World War II and in the years immediately after. The author, for example, was posted in 1947 to begin preliminary studies for the proposed Independence Hall National Park in Philadelphia, two years later moving to Richmond Virginia to become Regional Architect. On one occasion, after Saarinen had been selected, the author toured the site with the new architect. While there, they discussed the idea of retaining the Old Rock Warehouse, recently restored by the Park Service. Mr. Saarinen liked the idea of keeping the old stone building because he felt it helped give scale to his soaring arch. Unfortunately, the carefully restored landmark was later removed and no longer exists.”20

Eero Saarinen and J. Henderson Barr, 1948. Photographer: James “Scotty” Kilpatrick. National Building Arts Center collections.

Saarinen Round 2 Sheet B, 1948, features the colored pencil rendering by J. Barr of the Saarinen design; the Museum of Architecture is located on the left-hand side along the road leading to the Old Cathedral. National Park Service Photo, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

“You walk down a few steps through the little formal garden and into the Architectural Museum where there are many more interiors and scenes of the buildings of old St. Louis. From here your route takes you through the Historic Museum. This is not an ordinary museum with objects placed in glass cabinets with labels next to them, but rather a museum which, through animated exhibitions, sound tracks and other modern devices, brings to life Jefferson and his time.”21

Saarinen mentioned the museums again in a 1949 paper that was concerned with site restrictions being imposed by the railroads and the tunnel they demanded to take the place of the riverfront trestle:

(3) The Museums called for in the competition program include a large Historical Museum and a small Architectural Museum. Before these are built, it is obvious that we have to try to establish the Museum policy, i.e., the type of exhibits, the size of each, etc. The outcome of this might be a building 50% larger or 50% smaller. The outcome also may be that the Architectural Museum is built as part of the Historical Museum. These decisions will influence the design of the southern area of the Park.22

In Saarinen’s original plan and the scale model made in 1948 soon after he won the competition the architectural museum stands in the southern portion of the park, a large, rectangular midcentury modern box with limited areas of large windows on the west at the south end of the building and on the east at the north end. The building apparently was imagined as having two levels (which may have been restricted to the east side, while the west side was open from floor to ceiling to allow the display of large building fronts). An estimate of the measurements of the building, taken from the competition drawing and the model, would make it about 264 feet long by 58 feet wide, with a height of 35½ feet. The cubic footage would have been 543,576, in line with the competition booklet’s 500,000 c.f. requirement, but far less than the three million cubic feet Peterson had hoped for in Plan 8009 in 1937.

Architectural Museum, Saarinen Competition Entry #1 and 2, views from 3D computer model created by Bob Moore in 2015.

Saarinen Competition Entry 1948 Architectural Museum #1 and 6, views from 3D computer model created by Bob Moore in 2015.

Post-Competition and Diaspora

The Korean War and domestic financial readjustments after World War II put the St. Louis project on hold in 1949, and it was not revived until 1957. As historian Sharon Brown related in her administrative history of the memorial:

The Denchar Warehouse still stood south of the Old Cathedral, containing the iron and architectural fragments salvaged from the demolition of 1939 to 1942. For many years plans had called for an architectural museum to be built in the memorial with the fragments serving as the principal resource. Economic reality struck in 1957, however, resulting in Eero Saarinen dropping the Museum of American Architecture from memorial plans. During 1958, when hundreds of cubic yards of fill were spread on the site according to the grading plans, the warehouse had to be removed. Age and decay made the building difficult to maintain, so [Park Superintendent] Julian Spotts requested that the [architectural] fragments [housed in the Denchar Warehouse] be given away because they could not be used at the memorial. National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth approved the request, form letters were prepared and sent to local universities and museums offering the fragments at cost, and the Park Service staff developed a plan for disposal by the spring of 1958.23

The Smithsonian Institution selected one-third of the fragments before Walter Huber, chairman of the National Park Service Advisory Board, expressed concern to Director Wirth about the situation. Superintendent Spotts was told to stop further action until the Park Service could restudy the collection. Spotts noted, however, that every time a delegation studied the fragments, more material was marked for retention. Spotts wanted a final selection to be made. In August Wirth finally stated the Park Service policy governing the preservation of the fragments. He believed that every reasonable effort was made to use as much of the material as possible in the memorial and by donation to the Smithsonian Institution. The remainder of the fragments not taken by schools, museums, and historical societies would be disposed of when the Denchar Warehouse was razed. This served to allay Mr. Huber’s fears that valuable historic objects were being destroyed needlessly.24

By September 1958 the National Park Service decided which objects it wanted to keep. Within the next few months the Smithsonian Institution, the Missouri Historical Society, and other organizations hauled away selected items.25 In the winter of 1959, the Denchar Warehouse was torn down, ending all hopes of having a Museum of American Architecture on the memorial grounds.

In August 1958 Acting Regional Director M.H. Harvey sent the following memorandum to Earl H. Reed, a well-known Chicago preservationist who was then working as a supervisory architect for the Historic American Buildings Survey. It provides some insight into the thinking within the ranks of the National Park Service at the time regarding the large collection of architectural fragments and what should be done with them:

We have appreciated your continuing interest in our problem of selecting architectural fragments from the large collection stored in the Denchar Building in St. Louis. Your specialized knowledge of the value of this material has been very helpful.

You are aware of the pressure under which the Service is placed to proceed as rapidly as possible with development of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. An important and basic phase of the Memorial development requires filling of the site of the Denchar Building. Orderly and efficient development of the Memorial makes it necessary to carry out this work in the very near future.

On the basis of the Director’s decision that museum treatment of architecture should be confined to those phases which contribute to the Westward Expansion theme, representatives of the office and the area made a selection of the fragments to meet this need. As a result of your interest, however, the Director asked us to delay disposal of remaining material until we could re-examine this selection to make doubly sure that no important items useable in the development of the Memorial were overlooked. Accordingly, Regional Architect Roberson, Historian Johnson, and Architect Bryan re-examined the previous selection, and chose a number of additional items which they felt fully rounded out the requirements of the area. The Director then advised us he would ask you to review our final selections and make any specific recommendations, based on observations during your visits to the area, to cover possible omissions we may have made in our selections, particularly with reference to some large items which conceivably could be used in a decorative motif of the future Memorial museum which is in the Saarinen Plan. For your convenient reference in making such recommendations we are attaching copies of the original and supplementary lists.

So that we may proceed with the dual responsibility of preserving the material needed for the Memorial, and disposing properly of the surplus architectural fragments in advance of demolition of the Denchar Building, we should like to ask you to indicate any large objects or other fragments, in addition to those on the attached lists, which came to your attention during your recent visit, that you feel we should consider for retention to illustrate architecture in the Westward Expansion theme, or which have potential for decorative use in the future Memorial museum.

We do not consider it practical or in keeping with the character or treatment of the Old Courthouse to store or display a miscellany of large architectural objects in the small courtyards, re-entries, or the main floor corridors of the building. However, we shall devise suitable means of interim storage of those objects which, upon your recommendation, appear to fit with the presently defined needs of the area.

Because we are working against time, we shall appreciate very much having your suggestions by August 15, if at all possible. After we have removed all of the fragments, the retention of which we feel can be fully justified for Memorial purposes, in keeping with the Director’s policy for treatment of architecture in this area, and after the Smithsonian has completed its final selection, the balance of the material now stored in the Denchar Building will be available for transfer to other interested institutions, in accordance with National Park Service disposal policy.M.H. Harvey

Acting Regional DirectorP.S.

In addition to our original check list of architectural objects to be preserved by the National Park Service, and in lieu of “Supplementary Lists” indicated in the third paragraph above, we also enclose Mr. Bryan’s paper entitled “Suggested Media for Telling the Story of Architecture in Westward Expansion.” You will note that this includes reference to specific architectural objects in the Denchar Building which are additional to those in the original check list.26

By 1958 Charles Peterson was living in Philadelphia and still coping with the second disaster of his life, the razing of a large number of post-1820 buildings in the central city area in order to “cleanse” the area of non-Colonial and Federal era structures. Peterson was outspoken in his frustration at the decision to not only dump the idea of an architectural museum in St. Louis, but also for the memorial to divest itself of the artifacts recovered in the 1930s. He recalled:

“[The Park Service] decided [the collection] had little or no value. The collection was then offered to museums by the Park Service. To its surprise, there was a lively interest. The Smithsonian Museum in Washington got first choice. Dr. Anthony N.B. Garvan and I went out to St. Louis and selected enough specimens to fill a large truck. With the dispersal of the collection hope for a major architectural museum in St. Louis ended.”27

“The Park Service thought it was just junk, you see. I was away from there, and wasn’t there to defend it any more. They advertised, and museums came from everywhere, they took the stuff away, and the Park Service was surprised! Surprise! The Smithsonian got the first dibs, and the director [of the Smithsonian] got me and Prof. Tony Garvin, [who] was a big consultant there, and we went out, we took a great big truck, and we got the pick of the specimens, and then after that, everybody came and got the rest. And the Park Service didn’t know it was of any consequence.”28

Records of the demise of the collection are also included in memorial files that include monthly reports from the park’s superintendent to his superior, the regional director in Omaha, Nebraska.

“On May 5 and 6 Supervisory Charles E. Peterson with Messrs. Taylor and Garvan, Smithsonian Institution, and Mr. Earl Reed, member of the Historic Sites Advisory Board were here in regard to the disposal program for the contents of the Denchar Building. Architect Bryan and Historian Johnson participated in the conferences held. The Smithsonian Institution has shown interest in a large amount of the material and marked it for removal. At the end of the month the situation was still confused as to who would get what and when and until this is resolved we cannot contract for the demolition of the structure.”29

John Albury Bryan was still working as the park’s historian/historical architect. He organized a large exhibition of cast iron artifacts displayed in the east basement of the Old Courthouse in 1954 in an effort to generate public interest in the collection. He was certainly appalled at the idea of jettisoning most of the items collected from the riverfront demolition. His monthly reports detail his hard work in a rather matter-of-fact way: “During this month thirty-six (36) hours have been spent at the Denchar Building, re-arranging the architectural fragments and weeding out the material that was put in there after the demolition program for the Riverfront had been finished.”30

“Regional architect Roberson was here on July 7 and again on the 21 and 22. On the latter date he was joined by Mr. Earl Reed of the Historic Sites Advisory Board and Mr. Charles E. Peterson, Supervisory Architect (historical) EODC for further discussion of the disposal of the material in the Denchar building and UNIT XI of the Museum of National Expansion. Reports of all concerned have been made but not final determination.”31

“Since returning to duty here, most of my time has been taken up with the distribution of the architectural fragments at the Denchar Building among the schools, societies, and museums interested in preserving and using some of the many fragments. The largest lot was taken by the Smithsonian Institution who required one large van and half of another to transport their selection to Washington.”32

“Architect Bryan devoted most of the month to the disposal of objects at the Denchar building and by the close of the month the disposal program was complete. We are now ready to let a contract for the removal of ear-marked objects to the Old Courthouse and for the demolition of the structure. This will be deferred until the weather improves and a new Superintendent arrives.”33

In a November 7, 1958 memorandum from Superintendent Julian Spotts to the Midwest Regional Director of the National Park Service, these details were revealed:

Of the some two hundred Museums, Historical Societies and Architectural Schools notified of the availability of architectural fragments on an exchange basis, three replied with the following results:

- Davenport Municipal Art gallery made an inspection and declined;

- Michigan Historical Commission indicated an interest but did not follow up, and

- Iowa State College made a date for November 14 with the understanding that if they made a selection they would remove the material on November 14.

Thus far the Smithsonian Institution, the Missouri Historical Society, the Missouri Botanical Gardens, and the Illinois State Park Board have removed the materials which they selected. The St. Louis County Historic Building Commission indicated an interest in some of the glass but have not followed through; Washington University Architectural School made an inspection but declined; the James Foundation at St. James, Missouri have indicated an interest in one piece and if selected will pick it up next week; the local Museum of Transportation expects to pick up the farm wagon on November 12.

It is expected that all of the material selected by all agencies will have been removed by November 14. All of the above distribution has been supervised by Mr. Bryan of this office.

Upon removal of all material selected and it is definitely determined that there are no more takers, it is recommended that one contract be let for the removal and transportation to designated places in the Old Courthouse of the material which we have selected to retain, plus the demolition of the Denchar Building and the disposal of all unclaimed contents.34

Bob Moore looks over artifacts from the 1930s demolitions stored at Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville. National Park Service photo, Gateway Arch National Park.

Today, the location of many of the artifacts originally stored in the Denchar Building is unknown. Large items stored in the Old Courthouse were moved in 1991 to an off-site storage facility at Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville. The Denchar Building was demolished in 1959. Searches in the memorial archives have failed to turn up adequate lists of items from the pre-disposal period. The memorial does, however, have complete records of all of the items retained by the park in 1958. The items taken by the Smithsonian Institution in 1958 are still in their possession and are stored in a facility in Maryland.

In the new museum beneath the Gateway Arch, the author of this article tried to incorporate as much of the spirit of the Museum of American Architecture idea as possible, including the construction of a full scale reproduction of a French Colonial house, the recreation of a portion of William Clark’s Indian Gallery and Council Chamber, the reconstruction (utilizing surviving elements) of the Old Rock House, and the use of a cast iron building front graciously loaned by the National Building Arts Center. We also tried to incorporate architectural models throughout the space, including the large HO scale model of the riverfront in 1852.

These are no substitute for what might have been, and hopefully, someday, the National Building Arts Center can fulfill the dream Charles Peterson had in 1936 of making St. Louis an essential destination for those interested in learning about the history of American architecture.

To conclude our interview in 1994, the author asked Charles Peterson what he felt were his greatest failures and successes during his tenure in St. Louis. He answered: “Worst failure was losing the Rock House, and the whole collection [of architectural fragments], which would have gone into the Museum of Architecture. Triumph was, I think it was entirely due to me that the Cathedral is still on its original site, and that the courthouse was included in the park. And the historians didn’t want the courthouse. They didn’t like the project to begin with. Well, for obvious reasons. They made the greatest demolition the Park Service had ever done, justified by an act to save historic buildings. And old Luther Ely Smith was right in the middle of that.”35

Additional images

Endnotes

- Charles E. Peterson, Before the Arch: Some Early Architects and Engineers on the St. Louis Riverfront, pp. 4-5, c. 2002, paper in the Historian’s Files, Gateway Arch National Park.

- John Albury Bryan was born in 1891 in Ludlow, Missouri, and graduated from the Chillicothe Business College. He came to St. Louis in 1912 to study architecture, and in 1914 entered the atelier of the St. Louis Architectural Club to work under Guy Study. He completed his architectural studies at Columbia University in New York City, and served with the Signal Corps in World War I. Returning from the war, he worked with St. Louis architects George E. Kessler (who was chief landscape architect for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904), Louis LaBeaume and Eugene S. Klein. He took a position with the National Park Service in 1936, working until 1959 at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. He was involved in the restoration of the Old Courthouse, the Robert Campbell House, the Tower Grove House of Henry Shaw, the birthplace of Harry S Truman in Lamar, Missouri, and the boyhood home of Gen. John J. Pershing in Laclede. He was the most important force in the revitalization of the Lafayette Square neighborhood in St. Louis, where he purchased a house in 1949. He was the author of, among other tracts, “Lafayette Square, the Most Significant Old Neighborhood in St. Louis,” (1962) “A Walk Through Bellefontaine Cemetery,” and “The Private Places of St. Louis” (1964). His major publication was Missouri’s Contribution to American Architecture (1928).

- Oral History Interview with Charles E. Peterson, conducted by Bob Moore, Historian at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial at Mr. Peterson’s home/office in Philadelphia on October 22, 1994, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

- Oral History Interview with Charles E. Peterson, October 22, 1994.

- Charles E. Peterson, Before the Arch: Some Early Architects and Engineers on the St. Louis Riverfront, p. 12, c. 2002.

- St. Louis Star-Times, July 29, 1936

- Charles E. Peterson, “Museum of Modem Architecture: A Proposed Institution of Research and Public Education,” Octagon: A Journal of the American Institute of Architects, November 1936

- Charles E. Peterson, Before the Arch: Some Early Architects and Engineers on the St. Louis Riverfront, p. 13, c. 2002

- Charles E. Peterson, Before the Arch: Some Early Architects and Engineers on the St. Louis Riverfront, pp. 10-11, c. 2002

- Oral History Interview with Charles E. Peterson, October 22, 1994, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

- “A Description and Explanation of Plan 8009 for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial,” National Park Service Memorandum, October 1937, pp. 5-6, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

- RU 106, Series 9, Planning Records, Subseries 9.3, Interpretation Records, Folder marked “A”, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

- “Concerning a Museum of American Architecture Proposed for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, November 1937,” RU 106, Series 9, Planning Records, Subseries 9.3, Interpretation Records, Folder marked “B”, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

- Oral History Interview with Howard Gruber, engineer on the memorial project from 1937 to 1942, conducted by JNEM Historian Bob Moore on October 22, 1993. Note: Mr. Gruber’s comments upon reading the interview transcript on March 21, 1994, have been incorporated in brackets.

- Oral History Interview with Charles E. Peterson, October 22, 1994, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

- Charles E. Peterson, Before The Arch: Some Early Architects and Engineers on the St. Louis Riverfront, p. 12, c. 2002.

- Memorandum, Spotts for Director NPS, 19 October 1942, JNEM; John Bryan, JNEM – Its Origin … pp. 16-17, JNEM. Bryan, possessing high interest in preserving the salvaged material, worried that patriotism would carry off his treasured gleanings. The only precaution he could take consisted of keeping the public out of the Denchar Building. See Sharon A. Brown, Administrative History: Jefferson National Expansion Memorial National Historic Site, June 1984, p. 93 (this resource is available online).

- JNEM Competition Booklet, 1947, pp. 10 and 15, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

- Saarinen later boosted the height of the Arch to 630 feet.

- Charles E. Peterson, Before the Arch: Some Early Architects and Engineers on the St. Louis Riverfront, p. 14, c. 2002.

- Eero Saarinen, “An Imaginary Tour of the Proposed Jefferson National Expansion Memorial on the Mississippi River at St. Louis,” 1948, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

- Eero Saarinen, The Levee Plan Limits Our Freedom to Cope With Yet Unknown Factors in the Design of the Memorial, Page 2, Record Unit 104, JNEMA Records, c. 1930-1975 (Unprocessed Correspondence), July 15, 1949.

- Memorandum, Chief Research Historian to Superintendent JNEM, 10 September 1964, JNEM. See Sharon A. Brown, Administrative History: Jefferson National Expansion Memorial National Historic Site, June 1984, pp. 162-163 (this resource is available online).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- M.H. Harvey, Acting Regional Director, to Earl H. Reed, August 8, 1958, Gateway Arch National Park Archives, Planning, Maintenance, Preservation of Museum Exhibits, 1958

- Charles E. Peterson, Before The Arch: Some Early Architects and Engineers on the St. Louis Riverfront, p. 12, c. 2002.

- Oral History Interview with Charles E. Peterson, October 22, 1994.

- Memorandum, Monthly Narrative Report, Superintendent JNEM to Director, Midwest Regional Office, NPS, June 5, 1958, Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, Gateway Arch National Park Archives, RU 106, Box 26, Folder 21.

- John A. Bryan, Historian’s Monthly Report for June, 1958, Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, Gateway Arch National Park Archives, RU 106, Box 26, Folder 21

- Memorandum, Monthly Narrative Report, Superintendent JNEM to Director, Midwest Regional Office, NPS, August 11, 1958, Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, Gateway Arch National Park Archives, RU 106, Box 26, Folder 21

- John A. Bryan, Architect’s Monthly Report for Nov. 1, 1958, Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, Gateway Arch National Park Archives, RU 106, Box 26, Folder 21

- Memorandum, Monthly Narrative Report, Superintendent JNEM to Director, Midwest Regional Office, NPS, December 9, 1958, Superintendent’s Monthly Reports, Gateway Arch National Park Archives, RU 106, Box 26, Folder 21.

- Memorandum, Superintendent JNEM to Director, Midwest Regional Office, NPS, November 7, 1958, RU 106, Series 9, Planning Records, Subseries 9.3, Interpretation Records, Gateway Arch National Park Archives.

- Oral History Interview with Charles E. Peterson, October 22, 1994.